In response to the new Facebook guidelines I hereby declare that my copyright is attached to all of my personal details, illustrations, graphics, comics, paintings, photos and videos, etc. (as a result of the Berner Convention). For commercial use of the above my written consent is needed at all times.

(Anyone reading this can copy this text and paste it on their Facebook wall. This will place them under protection of copyright laws. By the present communiqué, I notify Facebook that it is strictly forbidden to disclose, copy, distribute, disseminate, or take any other action against me on the basis of this profile and/or its contents. The aforementioned prohibited actions also apply to employees, students, agents and/or any staff under Facebook’s direction or control. The content of this profile is private and confidential information. The violation of my privacy is punished by law (UCC 1 1-308-308 1-103 and the Rome Statute).

Facebook is now an open capital entity. All members are recommended to publish a notice like this, or if you prefer, you may copy and paste this version. If you do not publish a statement at least once, you will be tacitly allowing the use of elements such as your photos as well as the information contained in your profile status updates.

Thankfully, the rumor-busting website Snopes.com is already on the case with a thorough debunking of FPD. I can't really understand why anyone would need such a debunking, since the idea that one could vacate all responsibilities pursuant to a contractual agreement by simply saying so is a hustler-move that wouldn't even fly on a pre-school playground. Like most everyone, I imagine, I also haven't read the "Terms of Agreement" that I (digitally) signed with Facebook... though I'm like 1000% certain that nowhere in those Terms is a clause that says "If you decide at any point you don't like these Terms, just post it as your status and it's all cool, man."

One good thing about FPD is that it provided excellent fodder for discussion in my Political Philosophy class today, which was in part about "rights"-- what they are, where they come from and how (if at all) they can be philosophically grounded. I'm a good enough Derridean to recognize that all so-called rights are somewhat violently "declared" before they're grounded, justified, inscribed into law and protected. So, if people want to declare their right to privacy on Facebook, there's a little part of me that respects that. But don't pretend you've got the force of law behind you on this one. That's just crazypants.

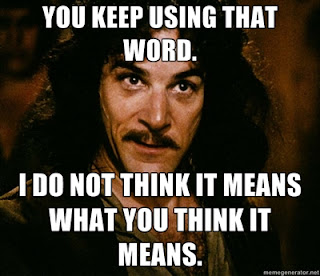

The other potentially good thing about FPD is that maybe, just maybe, a few people will take the time to actually look into the statutes, codes and conventions that are (erroneously) appealed to in the FPD statement. First, there's the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works-- not the "BerneR" Convention, as it is misspelled in the FPD statement-- which is an international agreement governing copyright. Second, there's the Universal Commercial Code (UCC), which basically serves the purpose of regularizing and harmonizing rules of sale and commercial transactions within and among our 50 states. Both documents are interesting, if somewhat dry, reads and can teach you a lot about how far we've come-- and how far there is yet to go-- in terms of our thinking about how to protect not only our privacy but also our (intellectual, literary and artistic) productions.

Perhaps the most hilariously WRONG element of the FPD statement is its appeal to the Rome Statute, which is the document that established the International Criminal Court and defines the jurisdiction of that court over human rights violations like genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and crimes of aggression. I can only assume, generously, that the original author of the FPD meant to appeal to the Rome Convention (and not the Rome Statute), which governs the protection of performers, recording artists and broadcasters. That is to say, whatever evil Facebook may be engaging in with the stuff I post on my profile, I doubt it rises to the level of a human rights violation.

Anyway, the wave of FPD rage will soon wane. Consider this my attempt to capture what people in my line of work call a "teachable moment."